EXPLORING STEELHEAD FLYFISHING’S LAST FRONTIER

Study a map of northwest British Columbia; what strikes you is the practically uncountable number of short streams cleaving the rugged mountains of the coast. Some named, some not, theyspill into the fjords of Chatham Sound, Portland Inlet, Work Channel, Douglas Channel, Devastation Channel, Gardner Canal and Grenville Channel, to name just a few in the labyrinthine system of waterways that define the region. The fly fisher tuned to chasing steelhead sees a vast area of opportunity and inexhaustible exploration. To be allotted only one lifetime hardly seems fair.

The majority of these streams are unreachable except by helicopter or motorized boat. A smattering of logging roads aid in access, but few connect with major roadways. For steelhead fishing, this is the last frontier: a tract located on the jagged edge of Canada’s renowned Skeena Country, too remote to have been developed, too harsh to sustain human population centers. In these hidden valleys, primal life exists as it has for millennia — and, where geography and climate are favorable, steelhead return to spawn each spring.

For most, the effort, logistics and expense required to fish these waters are prohibitive. If those aren’t deterrent enough, add unpredictability of run timing, inhospitable coastal weather, volatile stream flows and wild, toothy critters. Now the pursuit begins to look completely irrational. But, it’ll never be said with any conviction that fly fishing for steelhead has anything to do with rational behavior.

Consequently, for the fit and adventurous angler of modest means vulnerable to the call of the wild – and, perhaps, with a few screws loose – here is a most alluring siren song. As the sweet voices call, visions of wilderness solitude, untouched waters and hidden pools teeming with large, aggressive steelhead materialize. El Dorado lies beyond the next ridge, through the mist, teasing your thoughts, leading you headlong into ecstatic daydreams of leaping silver, luring you deep into the hushed rainforest.

A low ceiling of leaden clouds obscures the mountaintops and cold rain lashes our faces. Once on the water, the sound appears wider than expected and the small, open boat seems not quite adequate. We’re hunched against the stinging drops, drawn into the hoods of our rain jackets like turtles. Neil, our Nisga’a boatman stares ahead, unflinching, fit for the task by years of plying the local waters for crab, salmon and eulachon.

With me are brothers Martin and Tom Walker and Dustin Kovacvich. Dustin is manager and head guide at Nicholas Dean Outdoors in Terrace and this “adventure steelhead” program is his baby. A background in forestry, a love of wilderness and years of putting clients on steelhead make Dustin supremely qualified to lead our expedition. As fishing pressure builds on the Skeena tributaries, he has turned his sights on more difficult to reach venues and is continuously on the lookout for clients of the right profile – those willing and eager to put a little sweat equity into the venture. If presence in the boat can be construed as evidence of possessing the mettle, Martin, Tom and I have been accurately profiled and are more than ready to work up lather for a shot at the wildest of steelhead!

Tom resides in London, works in the film industry and, aside from spending some quality time with his brother, is looking to abandon the rush and pressure of urban life for a cobweb-clearing week of hiking and fishing – an antidote one part wanderlust and, hopefully, one part big-fish-on adrenaline.

Equally worldly, but decidedly rustic, Martin is an enigmatic mover in the San Francisco Bay Area technology scene. His concentrated passions include Chesapeake Bay retrievers, rod building, and like the writer, all the seductive trappings of fly fishing for large, wild, sea-run fish.

Also occupying a sizeable spot in the boat is Ruger, Dustin’s 130-pound Rottweiler-Akita mix and formidable bear alarm. The lush coastal valleys of Northern British Columbia comprise what is the last great and contiguous ursine habitat, not surprisingly known as “The Great Bear Rainforest.” Ruger could very well earn his kibble today.

Neil cuts the motor and the boat glides into the shallow water of a small bay. Ahead of us, a river mouth opens and tannic flow merges with the clear saltwater, a vision rendered silver and grey in the flat morning light. The river valley is tight, a dark cleft in the mountain flanks, its contours revealed by steep forested walls receding into a bank of swirling clouds snagged on the spired tops of spruce, cedar and hemlock. What lies beneath is cloaked in natural secrecy, long protected by the simple virtue of being unknown. The valley looks mysterious, inviting and a bit forbidding. Actually, it looks as if it could swallow us.

My mind starts racing with thoughts of angling glories but I’m quickly snapped back to present tense as Neil guns the motor.

“Call me on the radio at noon. Be careful for bears,” he shouts curtly and powers off, disappearing into the gray blanket covering the sound.

Standing waist-deep in the estuary water, I scan the tide grass beaches right and left of the river mouth. I’m relieved and disappointed. No brown, furry Volkswagens lumbering about. Yes, I do want to see one of those massive coastal grizzlies. Really, I do. But, not right now. Some other time, maybe…when I’m in the boat…at a safe distance…they don’t want anything to do with us, right? Right.

With backpacks, rods and Ruger, the four of us head upstream and into the forest. Large raindrops splat on our heads as we pick our way through the foliage and blow down. For a short time we follow a faint trail. Not far into the canopy it disappears and, aside from a piece or two of a timber cruiser’s survey tape, so do any signs of human presence. I’m filled with an eerie but enthralling energy. There is a slight element of danger in the air, but damp from rain and hiking perspiration, I’m eager to string a rod and cast a fly into the waters rushing within earshot. Mentally, and now physically, I’m fully engaged. I wonder if I could feel more alive.

Over the course of the day, between hiking over, under and around deadfall and dodging devil’s club, we fish a half dozen or so attractive pools, runs, riffles and slots. In this setting, steelhead are where you find them. Unlike in larger rivers, where steelhead may take up residence in the confines of a well-defined reach. Here, with less water overhead and smaller primary lies, steelhead may be scattered, oriented to structure and may move frequently. Though angling pressure here is nonexistent, large steelhead are still wild, wary creatures, loath to give away their presence to anyone or anything observing from above. Consequently, it can be fruitful to drop a cast into any likely looking niche, corner or pocket.

Fly choice for these smaller streams is very much affected by water-type. In deeper slots against high banks, under logs or around large rocks, small but heavily-weighted rabbit-strip leeches or Marabou Comets work well to dive deep and properly search through the holding areas – some of which are no bigger than an infant’s bath. In these situations, a short quick-sinking tip with a short leader will get your offering where it needs to be. Or, if flows are clear, a floating line and a 9 to12 foot leader is preferable.

With the latter configuration, you’ll cast upstream of your target, stack a couple of line mends to slow your drift, get the fly deep and free-drifting through the dark water. Keep a careful eye on the line. If it twitches, stops or jumps, strike quickly. If not, allow the line to tighten and the fly to swim crosscurrent and away from the lie. Takes often occur as the fly lifts and begins to swing – yes, just like nymphing for trout. But, this trout fishing is trout fishing for the biggest trout! A sharp focus on detecting subtle grabs in the early part of the presentation can mean the difference between a fishless day and hooking the fish of a lifetime.

But most enjoyable for me, when exploring these small streams, is rounding a bend and, like Magellan to his Strait, finding a classic flat water pool or choppy run with a few larger rocks breaking flow in the gut and tail. Here I can fish through in classic Pacific Northwest steelheading style with a larger swimming fly on a moderately-fast sinking tip, methodically covering the run in broad, concentric tight-line swings, each with a chance to conjure the big, silver dream.

The fly drops in against the far bank, skirts the remains of a fallen cedar and disappears into the tannin-stained water. Mend a sharp belly in the line; a wedge forms to start the presentation. The fly follows the wedge, initially swimming headfirst downstream, alive with fluttering feathers and flashing mylar. Then, as the wedge opens up, the fly orients broadside to the current, revealing its full silhouette to the holding fish. Lower the rod tip and lead the line toward the near bank. The fly reaches depth and simultaneously begins to flee crosscurrent from the deeper water, as if it had foolishly wandered into a lair of danger, has suddenly realized its mistake and is now stroking feverishly for safety.

Just such a scenario presented itself mid-afternoon, and provided one of the more memorable moments in our exploration.

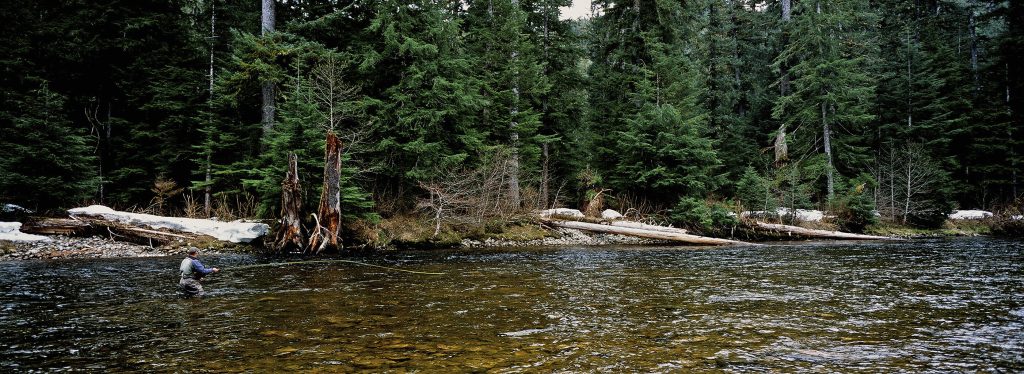

After several testy river crossings and detours through the brush along the forest’s edge, we came to a cobble bar about 50 yards long with a high bank opposite. The bar gave us optimum access to a juicy run featuring all the right ingredients: a strong choppy flow at the head, a steady stream at a walking pace through the middle and tail, and a strong drop and cascade at the bottom.

Along the high bank lay two fallen logs and an upright remnant base. Below the upright snag, the fallen trunks canted into the water, creating a current break. Abreast and below the logs, the river’s surface smoothed, indicating a deeper trough with a softer current than the adjacent flow. Just above the logs, the stream color transitioned from a luminous bronze hue, wherein each rock seemed to pulse in the low, diffuse light, to a black, opaque sink. If steelhead were in the run, they would be here, safely obscured from overhead predators and resting comfortably in the easy flow.

Tom fished through with a floating line and a small, but heavily-weighted orange fly, a relatively stealthy approach for our first pass. Martin followed with a sinking tip and a bright pink ostrich and marabou streamer tied in-the-round on a Waddington shank — an intrusive “Fight-or-Flight” special and tamer of many steelhead. None, however, would succumb this time. Neither fly found a fish.

We might have moved on, but Dustin had gone ahead to scout the next bend upriver and we agreed to await his return before leaving the run. Plus, we had hiked long and hard enough; Tom and Martin were happy to take a breath and allow the host a pass through the bucket.

Before I unfold the predictable sequence, know that it unfolded not at all predictably and is in no way an effort to boast on my own fishing prowess – which is certainly adequate, but by no means extraordinary. Both Tom and Martin fished through the run with finesse and, owing only to the vagaries of steelhead behavior, did not connect with a fish.

Knowing I’d have to do something different if I was going to entice a steelhead from this too-probable spot, I postulated the key would be to quickly sink a large dark fly into the slot against the logs – then swim it away in a flight of terror. In place of the 15-foot type VI sinking tip I had been using, I looped on a 10-foot LC13 tip, built a short 3-foot leader from 25, 20 and 15-pound nylon, and with a Perfection Loop, knotted on a 4-inch black, purple and blue shank fly. For what it’s worth, I’ve christened the fly a “Kingfisher”, designated so for its collar of kingfisher blue hackle, and to honor one of my favorite denizens of the river.

A couple of swings in, at exactly the suspected spot, the fish took with a solid pull as the fly began to move out of the dark water. I set the hook with a sharp sweep toward my bank and the fight was on. The drama had played out precisely as scripted, and I’d be lying if I said, in that instant, I didn’t feel a healthy amount of satisfaction. But from here, the production took an unexpected turn and, truthfully, became much more interesting.

After a series of frantic head-shakes and twisting maneuvers, the fish turned and bolted for the bottom of the run. Line left my reel in a loud metallic whir, the click-and-pawl check in my Hardy salmon reel doing little more than preventing an overrun. Fifty yards or so downstream, the river boiled and a translucent tail broke the surface and swirled, throwing a fan of spray. Then, as steelhead often do, in the far corner of the pool, as if debating the pros and cons of making haste for a safe haven somewhere downriver, the fish paused – and offered me a chance to regain line.

I cranked. The fish followed. But something was wrong. I lifted the rod tip and the line’s point of entry in the water stayed fixed. Damn! The fish’s run had threaded the line under a rock, branch, log – or who knows what – on the river bottom.

As I pondered my predicament, the fish rested, but only momentarily. Soon it was bucking and twisting again, straining the line under the snag and testing the integrity of the nylon and the strength of my knots. I feared the connection would be short-lived.

I began wading slowly toward the source of the problem but could see it would be near chest-high if I were to make it into the center of the run and not lose my footing. Not fancying a swim (with a camera on my shoulder), I put the idea of freeing the line aside.

How quickly grandeur had flipped. Under my breath, I muttered a string of the choicest blue phrases I could improvise, none of which, under such duress, were very imaginative, nor certainly worth repeating here.

The line continued to be pinned, but the rod top occasionally bounced which was a good sign. The fish was apparently still on and obligingly not in a full-on panic.

Just as I started to think the affair would end in disappointment, I heard a shout. “Hold on, Jeff.” I looked over my shoulder to see Martin advancing with a five-foot branch I had been using as an impromptu wading staff and had left on the bank behind us. “Before you do anything you’ll regret, let’s give this a try.”

After realizing he wasn’t going to club me for hooking a fish behind him, I recognized Martin’s intent. He quickly waded past me into the deeper water. I backed up and swung the rod around, allowing him to grab the line. With the bright yellow fly line in his left hand, he plunged the staff point into the river along the line with his right, feeling for the culprit. The flow was curling around his chest near the tops of his waders when he stretched his arm out and down. The current pushed and he shifted a bit. I thought, at any moment, he would start bobbing downstream. Or, at least, start taking on water. But he remained sturdy and dry. He held his position and prodded with the branch.

Then, to my amazement, the line came up in Martin’s left hand. He held it high above his head and I saw it dart toward the far bank. “There’s a fish on this line,” he stated, matter-of-factly. We all burst out in a mixed chorus of laughter and cheers.

The rest of the encounter was anti-climactic. Martin held the line momentarily tight until I reeled sufficiently to get the fish back on the rod and under tension. Moments later, I slid a sleek hen, maybe eight pounds, into the shallows and Martin grabbed her by the tail wrist. Her coloration echoed the conifer tannins in the river and her proximity to the sea was evident in the tones of blue, purple and magenta on her cheek. Despite living in such raw quarters, she was elegant and refined, an artful and elemental representation of land and water. I couldn’t help but feel like we had just found hidden treasure.

The rest of the encounter was anti-climactic. Martin held the line momentarily tight until I reeled sufficiently to get the fish back on the rod and under tension. Moments later, I slid a sleek hen, maybe eight pounds, into the shallows and Martin grabbed her by the tail wrist. Her coloration echoed the conifer tannins in the river and her proximity to the sea was evident in the tones of blue, purple and magenta on her cheek. Despite living in such raw quarters, she was elegant and refined, an artful and elemental representation of land and water. I couldn’t help but feel like we had just found hidden treasure.

After a few photos and a gentle release, the steelhead swam away, gliding toward center river, and seemed to vanish among the stones. Though we would not hook another fish the remainder of the day, our spirits were light and the hike back, several miles downriver, seemed less of a chore than it otherwise might have.

We rode in Neil’s boat back across the sound and, as the day darkened, our conversation fell silent. We had barely scratched the surface of possibility in a practically unexplored world. We were wet, hungry and more than a little tired. Each was looking out across the water to far shores, each in a different direction. I know exactly what they were thinking, because I was thinking it too.

Outfitter & Accommodations

Terrace, British Columbia, is the hub of the lower Skeena Valley and a perfect launching point for expeditions on the nearby coastal waters. Based in Terrace, Nicholas Dean Outdoors is ideally situated, equipped and staffed to operate a dedicated “adventure steelhead” program on the region’s remote rivers and streams. Depending on targeted water and guests’ desire (or tolerance) for immersion into the elements, overnight accommodations on this program may vary from rough wilderness shelters to bed and breakfast quarters in small native villages.

However, the majority of evenings are spent in contemporary but rustic comfort at NDO’s partner facility, Yellow Cedar Lodge. This fetching cedar beam construction is located in a secluded stand of timber overlooking the Skeena just minutes downstream of Terrace, and features the delicious cooking of Chef Alf Leslie. Many consider Alf’s fare, featuring fresh regional ingredients, and YCL’s appointments, the best package in the greater region.

We grab our gear and exit the boat. I sense our collective anticipation building. In his forestry days, Dustin surveyed this valley. He’s familiar with the layout and has it on trusted account from regional biologists this small watershed rears big fish. Steelhead here are thought to average 14-15 pounds. Considering Skeena system steelhead average 8-15 pounds and Nass watershed steelhead generally run smaller, for the greater region, this would be a very special lineage of fish.

Flies & Tackle

Eight to10 foot single-hand rods for 7-9 weight lines and 11-13 foot double-hand and switch rods for 6-8 weight lines will serve the angler well for the majority of the region’s remote coastal streams. As with all steelhead fishing, well-maintained reels with a high backing capacity are preferred. And those with a stout drag or a palmable rim can be handy in controlling fish in tight quarters around boulders, wood piles and above whitewater chutes.

Approach and presentation can vary greatly, depending on water type. Consequently, line systems which allow quick and easy switching from floating to intermediate to sinking tips in a variety of densities and lengths are highly recommended.

Fly choice is also dictated by water conditions and water type. In clean water, smaller bright flies on size No. 6-2 hooks weighted with beads, eyes or cone heads are often most productive. Fished across or quartered upstream on a floating line with a 9-12 foot leader tapered to 12-15 pound tippet, small, quicksinking flies are perfect for searching pockets and trenches.

For water with less than 2-3 feet of visibility and on broader runs and tailouts, larger swimming flies such as articulated leeches tied with marabou and/or rabbit strips fished on sinking tips with short 3-4 foot leaders (straight or tapered to 15 pound tippet) can be the way to go. Even the smaller streams on the coast host big steelhead and big steelhead love big flies if conditions are right.

Conservation Issues

In this age, no avid angler, hunter or outdoor enthusiast can call themselves a sportsman without being a conservationist, as well. Even in the most remote corners of the world, man’s industrial influence is being felt by wilderness inhabitants. In the greater Skeena region, including the outer coast, steelhead and salmon are vulnerable to impacts from developing resource extraction plans. The list of concerns is considerable: aquaculture interests are keen to set up open-pen operations in the region; commercial fish harvest continues, indiscriminate of sensitive or weak stocks; Royal Dutch Shell is pushing for development of a coal bed methane field in a vital tract that contains the headwaters of the Skeena, Nass and Stikine rivers; Enbridge is proposing a pipeline to deliver tar sands from northern Alberta to Douglas Channel where tanker traffic and inevitable spills would be disastrous to marine life; and private, for-profit hydro and water exportation interests are siting run-of-the-river dams and capture projects throughout northern British Columbia.

Make no mistake, the bigger Skeena and Nass systems, as well as the small streams on this rugged, but not impenetrable, coast are the last, best places for the largest steelhead on earth. Advancement of, or restraint from, large-scale industrial exploitation in the region over the next half-century may well determine their fate.

“One Life Time Hardly Seems Fair” by Jeff Bright was first published in the Contemporary Sportsman Magazine. Jeff has been my close friend and inspiration for a long time and maybe more important he converted me to spey fishing. Then what seems like a long time ago he spent ten days on the Skeena River teaching me how to spey cast. The only thing he forgot to mention was the other side of the river.

Jeff Bright is one of the finest freelance photographers and writers on the planet. A self-professed spey fishing fanatic, Jeff Bright’s writing, and photography have appeared in numerous major print and digital fly fishing magazines around the world. As a travel specialist, his expertise includes over a decade hosting and fishing the British Columba coast for steelhead and Pacific salmon in winter, spring, summer, and fall. When not leading the chase for steelhead in the Pacific Northwest, sea trout in Tierra del Fuego, Atlantic salmon in Russia, or sea-run char in the Canadian Arctic.

« Previous Post

Leave a Comment

No Responses to “One Lifetime Hardly Seems Fair by Jeff Bright”